ALPHABET MOVIE CLUB: Blade Runner

WEEK 2- "B"

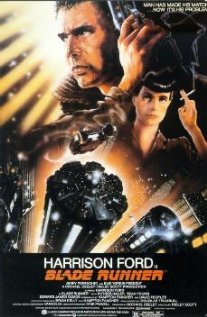

(Image: www.imdb.com)

Nominees: Breaking Away, The Blackboard Jungle, Blade Runner, Blood Simple, Bad Day at Black Rock

Winner: Blade Runner, and the chosen edition of the many versions was the Ridley Scott-approved "Final Cut" he restored and created in 2007.

Background: Hot off his breakout success of 1979's Alien, Ridley Scott brought his slow-boiling science fiction flair to a more domestic setting in 1982 with Blade Runner. Set in Los Angeles in the year 2019 and loosely based on the thematic elements of Philip K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Scott molded Blade Runner into essentially a noir gumshoe flick that just happens to take place in a dystopian sci-fi future.

With shades of Humphrey Bogart, Harrison Ford stars as Rick Deckard. Rick is a "blade runner," a cop specialized in hunting down and "retiring" (i.e. executing) rogue "replicants," organic robots that serve humanity as slaves and workers developed by the massive Tyrell Corporation. In true noir fashion, Deckard considers himself out of the game until four advanced model replicants (including Rutger Hauer and Daryl Hannah) capable of more emotion, thanks to uploaded memories, return to L.A. seeking answers. Along the way on the case, Deckard meets and develops a relationship with, Rachel (Sean Young), one of the advanced, yet civilized replicant prototypes from the Tyrell Corporation.

After an arduous production, Blade Runner, though misunderstood on its initial release by critics and audiences, has gone on to become a cult classic, national registered for artistic preservation, and a trailblazer for the "neo-noir" genre that has influenced art, music, anime, and science-fiction films. It was nominated for two Oscars (art direction and visual effects) but lost both. The film has been famously tinkered with a great deal and as many as seven different "cuts" of the film have been released to some extent. Scott himself took the reins to produce "The Final Cut" in 2007, which has been accepted as the definitive edition since.

Reaction: 5 STARS-- Sorry to flaunt my young-ish age, but Blade Runner was before my time. The first and only time I have seen it before was the 1992 "Director's Cut" on a 7-inch screen via VHS from a distance on a noisy charter football bus on a road trip 12 years ago. It was incoherent to understand then, but I relished the opportunity to really take it in this time, especially with the restored, remastered, and recalculated "Final Cut" from Ridley Scott's own hand. In this second "first" time seeing it, I was immediately impressed by the movie's style and production design, one of the best I've ever seen from that era or any other since. Scott succeeded in his goal to combine a true detective story in a wholly original science-fiction setting, while still adding shades of hubris from Greek drama and other moral philosophy questions. I loved the mash-up and complexity of those recipe combinations.

Blade Runner blends paranoia, corporate power, religious subtext, the fragile human mastery of science, creature mortality, and so much more into a svelte package that somehow stays under two hours, compared to a nearly four-hour movie like The Tree of Life, which had far less to say. The noir stuff wasn't too far either. If Scott laid the noir paint on any thicker (as he did with the removed Harrison Ford voice-over monologue), it would be too much. While it may not possess the requisite, shocking, and resonating ending twists of the science-fiction classics that came before it (Soylent Green and Planet of the Apes come to mind), Blade Runner is a movie that gets by on its looks at first, but really does blossom into something still worth examining afterwards.

LESSON #1: EYES ARE "WINDOWS TO THE SOUL"-- The entire notion of eyes acting as "the window to the soul" is examined existentially and literally with the many instances of visual imagery and eye symbolism present throughout Blade Runner. From the Voight-Kampff machine testing the emotional responses through eye movement in discerning a human from a replicant to the intentional human instinct of the body language of eye contact, the eyes are given great focus and emphasis. Our looks speak a thousand words and can convey an equal number of purposes as well.

LESSON #2: THE PERCEPTION OF REALITY-- Branching out from the eye symbolism, Blade Runner features human and robotic characters who each have a different lens when looking at the world. With manufactured memories and a short lifespan, things humans take for granted are deemed more precious to replicants (just look at their penchant for photographs), especially when compared to the burned-out perception that Deckard has of the bleek future setting. Also, with replicants that look and talk as humans do, in this world, you don't know if you are talking to a robot or flesh-and-blood. When does artificial become so well-created that it passes as real? Go ahead and restart that age-old "Deckard is a replicant" debate right now.

LESSON #3: THE SCOPE OF MORTALITY AND STRUGGLE TO SURVIVE-- Maybe we put too much personification into our science-fiction by wanting our creations to be a reflection of ourselves, but Blade Runner was not the first, nor the last, story to feature an artificial life form fighting for its own survival despite having abilities and strengths that exceed that of their inventors. Outside of artistic interpretations like this that bend our thinking, we don't identify our invented machines as having a soul, much less a sense of mortality. We see the ON/OFF switch and the plug outlet and wouldn't believe for a second that our smartphone is aware of our two-year service agreement to replace it down the road. With their programmed four-year lifespan, the replicants in Blade Runner possess an intriguing mortality that, like our own, is out of our control. They are subject to death, just as we are, and will fight for their own survival.