GUEST ESSAY: "Cidade de Dues:" A Manipulated Reality of Favelas

Cidade de Dues: A Manipulated Reality of Favelas

By Omar Cardoza

Introduction

In 2002, Cidade de Deus, otherwise known as City of God, was released in Brazil. It did not take too long before the film became internationally acclaimed, in fact this film was nominated for multiple Oscars although it did not win. The film’s narrative, filming techniques, and setting provide for a compelling argument that the whole story is in fact a true depiction of the favelas Brazil. Films and cinema can be a means to generate discourse between a reality presented to us through the screen and the actual reality of the world. This can cause changes not only to the individual but through enough exposure to a broader audience can cause changes at the societal level and “is extremely important and carries tremendous responsibility since believing that films can shape the collective imagination can (re)affirm or deny a preconception or even reinforce…” (De Medieros Marcato). Fernando Meirelles uses filming techniques and architecture to portray a realism of the favelas as not only a city or the setting of the film but also as a character that intentionally creates a cycle of drug abuse and violence among the younger generations of the City of God.

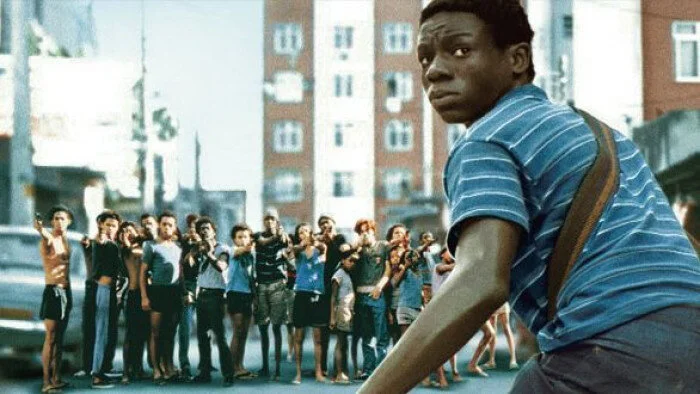

Fig. 1: Rocket caught in the middle of a war between gangs (pictured) and the police.

City of God Summary

Before we get into the discussion of the built environment in Rio de Janeiro’s favela’s, it may be helpful to quickly summarize the plot of the film Cidade de Deus (City of God). The film takes place in the City of God, a lower-class quarter in western Rio de Janeiro. This film follows the story of Rocket, or rather from the viewpoint of Rocket. He is the main character and the narrator throughout the film. The film is split into three distinct parts. The first part follows the actions carried out by the Tender Trio, a group, that includes Rockets older brother Goose, Shaggy, and Clipper, that robs businesses and gives back to the people. It is also the first time we meet Lil Dice as he hangs out with the trio. After a robbing a motel the trio splits apart to lay low from the police because they were framed by Lil Dice as the assailants of a massacre. Goose and Shaggy are shot dead and the Clipper ends up joining the church. The next part of the story is about the transformation of Lil Dice to Lil Ze the drug dealer and leader of a drug empire. While he is in power there seems to be a sort of peace and understanding with the residents of the favela until his best friend Benny, the only one that kept him under control is murdered. Lil Ze then loses his temper and attempts to take absolute control over the drug dealing turf and starts a war with an opposing party led by Carrot. It is during this time that he loses control and humiliates a man by the name of Knockout Ned who becomes important in the drug turf war. This then transitions to the last part of the film, riddled with countless shootings and deaths both Ned and Lil Ze meet their end. Rocket however was able to escape from the favela because of his association with the favela. He was caught in the middle of all the fighting and even got pictures of Lil Ze’s murder which secured a job for him as a photographer for a famous newspaper (Martin).

Architecture and Realism

The way Meirelles films the city, one can begin to understand and recognize the importance of the setting. The city becomes a character of its own, no longer just a passive background for gang wars and drug abuse, but a being that lures the youth into a seemingly inescapable and detrimental cycle with hopes of leaving poverty behind. In one word, cruel. Meirelles is not simply transporting us to the favelas, using cinematic language, he can completely immerse the audience to the fast-paced life of the slums. As a viewer, it not only makes you to enter a totally different world, but it forces you to confront the issues that come with a world so alien to many of us. One has very little time to adjust from scene to scene that you have to quickly adapt just as the characters in the movie have to, unfortunately for the character their ability to adapt to their environment is a matter of life or death

Fig. 2: Rocket reviewing the images he's taken as he faces a choice that could impact the rest of his life.

It is true that Meirelles hoped to transport the viewers from the screen to his visual depiction of the favelas. However, it is also important to note that the film was an adaptation to a novel of the same name by Paulo Lins. Lins identifies himself as a favelado, a resident of the favelas. He grew up during the time that crime was rising, and drug lords were entering the community. Lins memories are what inspired the main character of the film, Rocket. Stuck in between of all the crime and violence, it was his relationship with it all that provided an escape for him. But, at the same time Rocket is also the narrator of the film so it alienates him from the very world he grew up in. Rocket plays a very important role in the film as he becomes the viewers guide to the City of God. Only through Rockets point of view are we allowed to create connections to the characters and the spatial arrangements in the environment. Meirelles used this to his advantage to lend a factor of authenticity to the film, the only way to know about the events was to be part of the favela community. As a result, the way the favela is represented in the film is very interesting. It is depicted as an isolated place from the rest of Brazil which helps its role as a character become increasingly amplified. The favela becomes the only place that matters in the film and only the very fortunate, which are very few, ever leave. Both the novel and the film seem to be speaking from the residents inside the community through various film editing techniques.

Without a doubt, Meirelle’s editing in the film is at the very least striking. Sergei Eisenstein, a Russian film director, film theorist, and quite possible best known as the father of montage created an editing technique that would allow the viewers to see a sequence of multiple unrelated/neutral frames to express an unstated meaning(Todd). Take for example Meirelle’s application of montage in the opening scenes of the film, it starts off with the depiction of a Latin area going about their daily business through the eyes of a chicken. A knife being sharpened, the chicken staring at you, vegetables and drinks being prepared, the chicken, other chickens being killed and prepped for food, the chicken desperately trying to escape. In fact, the way the chicken sees the built environment can provide an interesting depiction of the city. The city is inescapable, I base this statement on two major observations of the built environment. The first, which may be a little obvious comes to the scale of the building when compared to the chicken. The houses/shacks loom over the camera almost as if they are pressing down with all their weight. Similarly, the city can be viewed as an entity that crushes the innocence out of the children and desensitizes them to all the violence. Secondly, the path that the chicken takes is convoluted and seems to resemble a maze, again further cementing the idea of the favelas being inescapable. However, it also it provides another aspect to the spatial relations in the movie. There seems to be a lack of differentiation between public and private space. Only in the beginning, there is a clear difference between a family’s private space (house) and the public (soccer field. The chicken symbolizes the people of the favelas, especially the younger generations as they the ones most deeply affected by the internal forces of their environments. This is directly related to the scene of other chickens lying dead as they are prepared for cooking. It shows the way of life during the age of the film, death was a normal part of life for the gangs of the favelas, the gang members have grown accustomed to seeing their own kind being slaughtered.

Fig. 3: Opening scene showing the complexity and scale of the labyrinthian favelas

How is this applied to the architecture of the film and to the architecture of the favelas? Perhaps the biggest turning point for the antagonist of the film is when Lil Dice decides to take over Blacky’s drug dealing territory. This cause the transition of Lil Dice to Lil Ze the gang leader and one of the biggest drug dealers of the film. However, Meirelle’s does an excellent job in explaining how Blacky came to be a drug dealer as well. The apartment scene which is widely known for its use of mise-in-scene can clearly depict the degradation of the city. The apartment cycles through four owners, a mother, Blacky, and finally Lil Ze. The film explains that the mother began selling drugs to raise her daughter. Right away we see that the city offers a poor infrastructure the middle- and lower-class people. However, by analyzing the interior of the apartment we can tell that the mother is trying in creating a home for her family, we see tables, chairs, appliances, and food. The next owner, Big Boy, a client of the mother, forcefully takes over her “amateur” drug operations and expands it. This is reflected in the missing furnishings of the apartment as he needs more space to allow his delivery boys to quickly access his drugs. We see a transition from home to a barren drug operating facility with little to nothing in the interior, the only thing that remains is the table and a couple of chairs. After analyzing the apartment, we can realize that the apartment is a symbolic representation of films environment.

Conclusion

Meirelles presents the City of God as a crime ridden, drug infested, slum, shanty town but in actual reality it is so much more. Lins takes pride in being a favelado, many residents of similar communities share the same experience. However, his use of filming techniques intertwined with the architecture of the favela can begin to offer a fabricated but somewhat realistic view of the City of God. Not only does this have effects on the audience but it has affected the actual residents of the favelas as well. By offering an insider’s exclusive take of this community, many have begun to take interest in the favelas as an exotic destination for travel. Due to this, many changes have begun happening in the favelas such as permanent police surveillance for criminal activity. Meirelles created a complete work of art that helped boost the Brazilian film industry, and it should be treated as such. We must remember that there is a significant difference between fabricated realities and true reality.

Fig. 4: Transformation of a housing unit from a family home to a drug safe house. Left is at the beginning of the film and right is at the end (30- year span)

Bibliography

City of God. Miramax Films, 2003.

De Medieros Marcato, Raquel. “Genre in evidence: Does the film, City of God, manipulate reality?” [online article], 452ºF. Electronic journal of theory of literature and comparative literature, 2, 80-95 (2009): http://www.452f.com/index.php/en/raquel-de-medeiros-marcato.html

Dovey, Kim, and Ross King. “Informal Urbanism and the Taste for Slums.” Tourism Geographies 14, no. 2 (2012): 275–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2011.613944.

Fiorelli, Lindsey, "What Movies Show: Realism, Perception and Truth in Film" (2016). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1715. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1715

González-Casanovas Roberto J. “Reconfiguring Brazil Interdisciplinary Essays.” New Zealand Centre for Latin American Studies, 2012.

James, Mathew R. “Film Form Analysis - City of God (Opening Sequence).” Medium, 26 June 2016, medium.com/@MattyJay/film-form-analysis-city-of-god-opening-sequence-3c675ced1c7.

Martin, Brian. “City of God.” Brianair.wordpress.com, 7 June 2010, brianair.wordpress.com/film-analysis/city-of-god/.

“Realism.” Film Reference. Accessed November 26, 2019. http://www.filmreference.com/encyclopedia/Independent-Film-Road-Movies/Realism-THEORIES-OF-REALISM.html.

Safeena. “The City of God (2003) – Editing.” Filmutopia, 22 Apr. 2017, filmutopiablog.wordpress.com/2016/02/29/the-city-of-god-editing/.

Todd, Jeffrey M. “Eisenstein’s Film Theory of Montage and Architecture.” (1989). Georgia Institute of Technology. Accessed September 21, 2019. https://smartech.gatech.edu/bitstream/handle/1853/21653/todd_jeffrey_m_198912_ms_333258.pdf

LOGO DESIGNED BY MEENTS ILLUSTRATED